|

| Rivas Bomberos in front of the WI engine. |

This July I was fortunate enough to spend a little time with

some firefighters (bomberos) in Nicaragua.

Despite a language barrier, I felt at home with the firefighters of Rivas and Managua,

finding that once we started to talk shop, I could communicate effectively with

sound effects and emphatic gestures.

|

| Pumper from Canada |

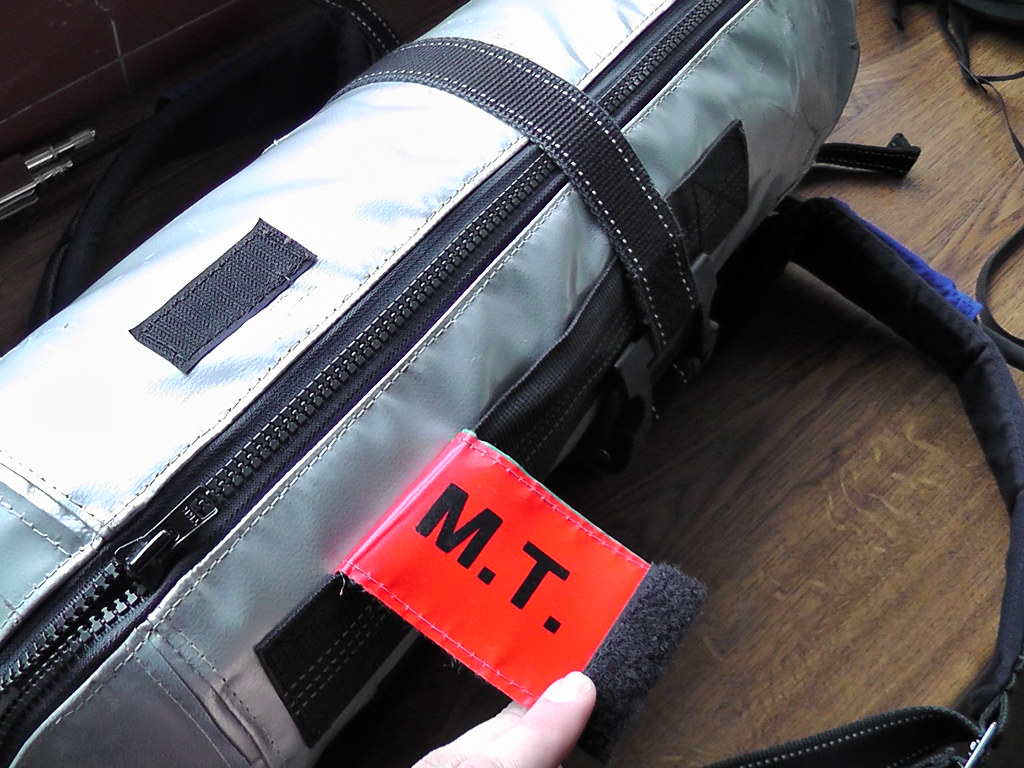

Most of Nicaragua’s

fire equipment is inherited from other countries, especially the U.S.

and Canada, so

they’re working with nozzles and pumps I am familiar with. In fact, one of the trucks at the Rivas station was from Buffalo

County WI,

which just goes to show how small this world really is.

|

| Fire Station in Rivas |

While I was visiting the Station in Rivas I met Cesar

Guevara, a Captain of the fire department in Managua,

and in charge of Ambulance operations there. On top of that he was a doctor,

and spoke English, relieving my friend Riley from her interpreter duties. Thanks again Riley.

Captain Guevara had brought an ambulance from Managua

to staff the medical station at the international master’s surfing competition,

and stopped in the Rivas Fire Station to pay his respects. This was incredibly

good luck for me, as I was invited to come shadow on the ambulance for the

surfing competition.

|

| Ah, the fantastic views offered at an international surfing competition. |

While watching surfing and taking patients to the nearest clinic

for stitches (nothing major) was cool, the best part of the competition was

being able to talk to Captain Guevara.

I’ll briefly breakdown some of the firefighting

numbers/facts he gave me.

Nicaragua

is protected by a government fire department, within which there are

professional and volunteer firefighters. This is a country wide system, meaning

that there isn’t a Managua Fire Department, or a Granada Fire Department,

instead they are all one organization. The exception to this is some volunteer

departments, like Rivas, which do not operate under the Nicaraguan government

fire organization.

Although the fire service’s budget is small compared to Police,

Immigration, or the Jail system (all four of these systems operate under one

branch of government) only the firefighters are popular with the people. I

guess some things are the same no matter where you go.

Bomberos (firefighters) work for 48 hours, then have 48

hours off, work for 72 hours, get 72 hours off and then start back over again with

the 48s. So they are at work half of the time.

Nicaragua

has a population of roughly five million. During the day (when people are at

work) the city of Managua swells to

hold two million of those people. And they have seven fire stations. Which

isn’t very many…. At all.

In the end I didn't get to spend nearly as much time with the Bomberos as I would have liked, so hopefully I will return to Nicaragua before too many years go by. Maybe I'll learn Spanish too, who knows.